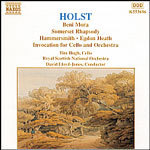

Holst: Orchestral works (Including Invocation for Cello and Orchestra)

$25.00

Out of Stock

$25.00

Out of Stock6+ weeks add to cart

GUSTAV HOLST

Holst: Orchestral works (Including Invocation for Cello and Orchestra)

Tim Hugh (cello) / Royal Scottish National Orchestra, David Lloyd-Jones, conductor

[ Naxos / CD ]

Release Date: Friday 15 February 2002

This item is currently out of stock. It may take 6 or more weeks to obtain from when you place your order as this is a specialist product.

"Sherbakov rises magnificently to the considerable technical and expressive demands of Respighi's piano writing"

- Fanfare

"All are played with finesse and character by the RSNO....Invocation eloquently played here by the cellist, Tim Hugh.....In short another Naxos winner"

- BBC Music Magazine

"This disc, superbly recorded in the Henry Wood Hall, Glasgow....Particularly beautiful is the performance of Somerset Rhapsody"

- Gramophone Editors Choice June 1998

Looking back over the twentieth century one might wonder how Gustav Holst came to be such a seminal figure in British music on the basis of so few familiar works. Today's casual concert-goer or record-buyer would be challenged to name three or four of his compositions. In fact he wrote several hundred in practically every genre. Singers will know part-songs and wind-players the military-band suites, but his modern reputation rests on The Planets, The Hymn of Jesus, and perhaps the ballet music to The Perfect Fool. These few pieces not only underpin Holst's present position but were all written in the surprisingly short period when he received, or in his view endured, popular approval. The Planets was first performed in 1918, The Hymn of Jesus in 1920 and The Perfect Fool in 1922. Outside this period of public favour things were different: hitherto he was young, up and coming, needing to feed himself, find his own voice and make it heard; afterwards, being the personality he was, the price of forging ahead was to leave the public and the musical establishment behind. This caused Holst no heartache at all for there was little chance that critical endorsement would ever compromise his artistic tenets.

This recording neatly covers in chronological order these outer two periods (three pieces from each of them), revealing some clues as to why Holst was so central to English music of the early twentieth century. In this one man's music can be traced all those musical currents which fed and energised the musical renaissance in England at that time. A man who never stood still, who was driven to experiment, who needed no cheering from the touchline, a man with his mind open to the musical revolution that was under way in Europe but in whose ears still rang the modal inflexions of folk-song, the rhythmic freedom of plainsong and the exhilarating counterpoint of the Tudor age.

The Somerset Rhapsody (1906-7) was written at the suggestion of the great folk-song collector Cecil Sharp and was Holst's first real critical success. Had he then decided to climb aboard the English pastoralists' hay-wagon he might well have shared the now well-composted reputation of that school, but already there were signs of where Holst would be going: those repeated scalic bass lines, the rising trumpet-calls and his love affair with contrapuntal ingenuities. Yet there are backward glances to what his daughter Imogen calls his 'early horrors'; some rather trite thematic development and residual patches of overripe Wagnerian harmony. He quotes four different songs: his own acknowledged favourite the Sheep Shearing Song, High Germany, The True Lover's Farewell and The Cuckoo, all presented in full at least once but overlaying each other to varying degrees in a tight musical structure.

Beni Mora (1909 -10) or Oriental Suite could, like the Somerset Rhapsody, convey in its title the suggestion of diversionary salon music. Holst does to some extent indulge the listener in some picture-postcard scene painting but he could never be content with just that. The premiere drew some hisses as the audience realised that Holst was not presenting his holiday snapshots in quite the way that prevailing musical conventions required. The First Dance is the most conformist, complete with the nasal sound of the cor anglais, 'oriental' intervals and impassioned arabesques not dissimilar to Borodin. In the Second Dance carefully selected instrumental groups; timpani, bassoons, low flutes and upper strings, create a scene of stillness, mystery and some menace. The finale, subtitled In the Street of the Ouled Naïls, reveals something of the emerging Holst.

Scenting a musical challenge, he introduces a short evocative riff in the low flute which he had apparently heard an Algerian native instrumentalist intone for 21/2 hours. Holst repeats it a mere 163 times, stretching his technique and harmonic ingenuity to the limits, while creating a hypnotic atmosphere of torrid, highly charged night air vibrating as the sounds of an approaching Arab procession mingle with those from the dance halls and cafés lining the street.

Invocation for Cello and Orchestra (1911) also evokes a nocturnal atmosphere, even to the extent of having as an original title A Song of the Evening. It too looks forward and backward. Romantic harmonies still linger, but the free rhythm of the introduction, and the crystalline woodwind colours pre-echo Venus from The Planets, a work that would occupy much of the next few years. After a few early performances Invocation became lost amongst Holst's papers where it remained for some sixty years with the encouragement of his daughter Imogen, who regarded it as 'not of any value in itself'.

After the next few years, during which the public and the critical establishment fell into step with him, Holst strode on ahead. The Fugal Overture (1923), first used as an overture to the opera The Perfect Fool, shows further evidence of his lifelong musical preoccupations. Contrapuntal ingenuity and asymmetric rhythms are set in a concise, balanced yet totally original formal structures. The scoring demonstrates an economical and individualistic use of the orchestral palette. Its initial reception was mixed; some praising its good humour but others ominously regretting Holst's lapse into asceticism and perverse exercises in the contrapuntal style.

The even colder reception given to Egdon Heath (1927) failed to perturb Holst who, for the rest of his life, considered it his best work. Above the score is a quotation from The Return of the Native by the work's dedicatee Thomas Hardy; 'A place perfectly accordant with man's nature - neither ghastly, hateful nor ugly; neither commonplace, unmeaning nor tame; but like man, slighted and enduring; and withal singularly colossal and mysterious in its swarthy monotony'. Holst was obviously fascinated by the challenge of recreating such an elusive yet finely drawn atmosphere and there may be an uncharacteristic note of self-justification in his anxiety that this quotation should always be in the work's programme notes.

Hammersmith (1930) was commissioned by the BBC for their Wireless Military Band and is played here in the wind-band instrumentation. Holst then made an orchestral version for its first performance, sharing the programme with the London premiere of Walton's Belshazzar's Feast. This unlucky coincidence may account for its subsequent obscurity as an orchestral work, Holst lived and worked for much of his life in West London and this musical tribute to the area contrasts the inexorable slow progress of the Thames with energetic bustle of the then energetic street-life on its banks.

- Christopher Mowat

Tracks:

Somerset Rhapsody, Op.21/1

01. Somerset Rhapsody 09:41

Beni Mora (Oriental Suite), Op.29/1

02. First Dance 06:17

03. Second Dance 03:58

04. Finale: In The Streets Of The Ouled Nails 07:11

Invocation for Cello and Orchestra, Op.19/2

05. Invocation For Cello And Orchestra 10:14

Tim Hugh, cello

Fugal Overture, Op.40/1

06. Fugal Overture 05:09

Egdon Heath, Op.47

07. Egdon Heath 12:49

Hammersmith, Op.52

08. Hammersmith 13:41