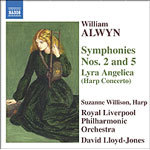

Symphonies Nos. 2 and 5 / Harp Concerto, 'Lyra Angelica'

$25.00

Out of Stock

$25.00

Out of StockSpecial Import add to cart

WILLIAM ALWYN

Symphonies Nos. 2 and 5 / Harp Concerto, 'Lyra Angelica'

Suzanne Willison (harp) / Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra / David Lloyd-Jones, conductor

[ Naxos / CD ]

Release Date: Monday 19 September 2005

This item is only available to us via Special Import.

"This disk can be placed alongside those of the composer and Richard Hickox and its price as well as its performance quality make it a valuable contribution to the Alwyn discography."

MUSICWEB RECORDINGS OF THE YEAR (2005)

"This disk can be placed alongside those of the composer and Richard Hickox and its price as well as its performance quality make it a valuable contribution to the Alwyn discography."

- Dave Billinge, MusicWeb International, September 2005

"You can safely use this recording to represent the orchestral Alwyn on your shelves. It is a stronger and more substantial mix than the valuable two piano concertos Naxos CD issued last month. The present CD represents an exciting harbinger for the rest of the series including symphonies 1, 3 and 4 ... and watch out because 4 is a real sonic spectacular."

- Rob Barnett, MusicWeb International, August 2005

William Alwyn was born in Northampton on the 7th November 1905. He studied at the Royal Academy of Music in London, where, at the age of 21, he was appointed Professor of Composition, a position which he held for nearly thirty years. Amongst his works are five symphonies, concertos for flute, oboe, violin, and harp and two piano concertos, various descriptive orchestral pieces, four operas and much chamber, instrumental and vocal music. In addition to this Alwyn contributed nearly two hundred scores for the cinema. He began his career in this medium in 1936, writing music for documentaries. In 1941 he wrote his first feature length score for Penn of Pennsylvania. Other notable film scores include the following: Desert Victory, The Way Ahead, The True Glory, Odd Man Out, The History of Mr Polly, The Fallen Idol, The Rocking Horse Winner, The Crimson Pirate, The Million Pound Note, The Winslow Boy, The Card, and A Night To Remember. In recognition of his services to the film medium he was made a Fellow of the British Film Academy, the only composer ever to have received this honour. His other appointments include serving as chairman of the Composers' Guild of Great Britain, which he had been instrumental in forming, in 1949, 1950 and 1954. He was a Director of the Mechanical Copyright Protection Society, a Vice- President of the Society for the Promotion of New Music (S.P.N.M.) and Director of the Performing Rights Society. For many years he was one of the panel reading new scores for the BBC. The conductor Sir John Barbirolli championed his first four symphonies and the First Symphony is dedicated to him.

Alwyn spent the last 25 years of his life in Blythbough, Suffolk, where, in those tranquil surroundings, he concentrated on two operas, Juan, or the Libertine and Miss Julie. In addition to chamber and vocal music, he composed his last major orchestral works there, the Concerto Grosso No. 3, commissioned as a tribute to Sir Henry Wood on the centenary of his birth in 1964 and first performed at the London Promenade Concerts that year by the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by the composer, the Sinfonietta for String Orchestra in 1970 and the Symphony No. 5 'Hydriotaphia' during 1972-73. When not writing music he spent his time painting and writing poetry and an autobiography entitled Winged Chariot. He died on the 11th September 1985 after various illnesses just two months before his eightieth birthday.

Andrew Knowles

Symphony No. 2, the second of my cycle of four symphonies, was in complete contrast to No. 1. All vestige of classical form was abandoned. I conceived it in one continuous movement only broken by a momentary pause before Part II where the music plunges into a tumultuous Allegro in contrast to the quietly ecstatic section that preceded it. The symphony concentrates on the development of a single main motif, accompanied by ominous triplet interjections on the timpani, building to a huge climax which finally resolves into a tranquil, almost modal pianissimo coda. I wish I could say that the work (first performed in 1953) was an immediate success but, although warmly received by the audience, it met with considerable opposition from the critics who were all at sea when faced by my symphonic innovations, neither understanding my harmonic frankness (steadfast adherence to the basic essentials of tonality and melody) or the new freedom of my formal design ... [the Second Symphony] is my favourite of the five.

(from Winged Chariot: An Essay in Autobiography

by William Alwyn)

Symphony No. 5 was commissioned by the Arts Council for the 1973 Norfolk and Norwich Triennial Festival. A gap of fourteen years had elapsed since the composition of my fourth symphony; a period almost totally occupied in the composition of my two operas, Juan, or the Libertine and Miss Julie. During that time my attitude to symphonic writing had radically changed. My aim now was to compress the inordinate length of the late-romantic four-movement symphony into a short one-movement work while still preserving the dramatic contrasts of the traditional symphonic form but confining it to four brief sections.

This fifth symphony is dedicated, appropriately 'to the immortal memory of Sir Thomas Browne (1605- 82)', physician, philosopher, botanist and archaeologist, Norwich's most famous citizen, whose great elegy on death was first published under the title of Hydriotaphia: Urn Burial, or a Discourse of the Sepulchral Urns lately found in Norfolk (now more generally known by its sub-title: Urn Burial), and whose own mortal remains lie buried in the magnificent church of St Peter Mancroft in the heart of the city.

Although each section is headed by a quotation from the book, the symphony is not intended as 'programme music'; Browne's wonderful prose sets the mood of each section and is an expression of my personal indebtedness to a great man whose writings have been a life-long source of solace and inspiration.

The upward-thrusting three-note figure of the opening Allegro on which the entire symphony is based can immediately be linked with the quotation: 'Life is a pure flame, and we live by an invisible sun within us.' After a momentary silence, the second section is introduced by the sinister sound of tubular bells, muted string harmonics and an insistent reiterated harp note: 'But these are sad and sepulchral pitchers, which have no joyful voices; silently expressing old mortality, the ruins of forgotten time.' The close of this section sinks to a whisper of sound-a high trill on the solo violin, brutally interrupted as the music plunges into a brief scherzo section: 'Simplicity flies away, and iniquity comes at long strides upon us.' This resolves into a return of the initial crescendo, the three-note figure of the opening section. Then the distant tolling of tubular bells (pianissimo) initiates the solemn tread of a funeral march based on a final majestic quotation: 'Man is a noble animal, splendid in ashes, and pompous in the grave.' A long and expressive melody builds to a fortissimo climax (maestoso). As the climax fades, the motto theme is heard for the last time, and the symphony sinks to rest in a mood of serenity, only disturbed at the last by the dissonant accent of muted horns.

'Lyra Angelica' (Angel's Songs) was inspired by my intense love of the seventeenth-century English metaphysical poets, George Herbert, Richard Crashaw, Henry Vaughan, John Donne and Thomas Traherne, of whom Giles Fletcher is probably the least known today, although his masterpiece, the epic poem Christ's Victorie and Triumph (1610), was the direct inspiration of Milton's Paradise Lost. My Concerto for harp and strings is a cycle of four elegiac movements, each illustrating a quotation from Fletcher's text:

1. (Adagio) 'I looke for angel's songs, and hear him crie.'

2. (Adagio, ma non troppo) 'Ah! Who was He such pretious perils found?'

3. (Moderato) 'And yet, how can I let Thee singing goe,

When men incens'd with hate Thy death foreset?'

4. (Allegro giubiloso-Andante con moto) 'How can such joy as this want words to speake?'

In my interpretation of these lines I have tried to capture in musical terms the sensuous imagery and mystical fervour of the poem as a whole. The concerto is of symphonic proportions but free and harpsodic in style. A detailed analysis of its complex construction in this case is inappropriate as it might tend to distract the listener from the rapt mood I have tried to sustain by interweaving the solo harp and strings into a continuous web of luminous sound.

- William Alwyn