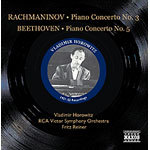

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 / Rachmaninov: Piano Concerto No. 3

$25.00

Out of Stock

$25.00

Out of Stock6+ weeks add to cart

LUDWIG van BEETHOVEN / SERGEI RACHMANINOV

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 / Rachmaninov: Piano Concerto No. 3

Vladimir Horowitz (piano) / RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra / Fritz Reiner, conductor

[ Naxos Historical / CD ]

Release Date: Sunday 11 September 2005

This item is currently out of stock. It may take 6 or more weeks to obtain from when you place your order as this is a specialist product.

"On Naxos comes the second account Horowitz made of D minor Concerto and, like its coupling, it remains one of the classics of the gramophone. Horowitz was unrivalled in this concerto. It is among the most classical of readings and Reiner is a totally like-minded partner. Good new transfers." Penguin Guide

"Superb liner notes from Jonathan Summers and Mark Obert-Thorn has done a fine job with the sound."

(MusicWeb Oct 2005)

Born in the Ukraine in 1903, Vladimir Horowitz entered the Kiev Conservatory at the age of nine, where his teachers were Sergei Tarnowsky and Felix Blumenfeld. He played in Russia from 1920, but then left the country in 1925. After his Berlin and American débuts in the late 1920s Horowitz had a unique career involving many triumphs and four periods of retirement from the concert stage. His last concerts were given in the mid-1980s and he died in New York in 1989.

At the beginning of the 1930s Horowitz apparently only had five piano concertos in his repertoire. Tchaikovsky's First, Rachmaninov's Third, Brahms's Second and both the concertos by Liszt. Throughout his long career Horowitz did not play much of Beethoven's music; some of the Piano Sonatas and the Thirty-two Variations in C minor, WoO 80. In November of 1932 Horowitz received an invitation from the conductor Arturo Toscanini to perform Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat, Op. 73, the Emperor, with the New York Philharmonic Orchestra in April of the following year. Horowitz admitted to not knowing the work and had to learn it specifically for the performance. Before the New York concert, Horowitz tried it out in Chicago with conductor Frederick Stock in April 1933. The Boston critics felt Horowitz did not have an understanding of the work, that there was something missing, that it was 'neither Horowitz or Beethoven'. Horowitz was not sure of his interpretation of the work, but when he met Toscanini in New York, they had similar ideas about tempos, and with only one rehearsal gave the performance on 23rd April. Horowitz did not often play the work in public, but in the early 1950s, with the introduction of the LP record, he recorded the work with Fritz Reiner and the RCA Victor Symphony Orchestra. Horowitz is quoted as saying that Reiner liked his playing. 'He said that this was an aristocratic Emperor; that everybody else pounded it out.' It is true that this is a much more 'classical' reading of the Emperor than one would expect from Horowitz. It has clarity and poise, and in this new transfer Horowitz's beauty and variety of tone can at last be heard. Contemporary critics were rather dismissive of Horowitz's recording, noting his technical mastery but complaining about the sound quality more than anything. It is a fine performance by both pianist and orchestra and interestingly, Joan Chissell wrote in 1990 that 'More than any of Horowitz's records to come my way in recent years, this one leaves me in no doubt as to why he grew into a legend.'

At the beginning of his career the Piano Concerto No. 3 in D minor, Op. 30, by Rachmaninov became Horowitz's calling card. Although the work had been dedicated to Josef Hofmann, he and many other pianists did not play it at this time. Horowitz played it in 1927 with Karl Muck in Hamburg, and in Boston in March 1928 with Koussevitzky. During the 1929-30 season when he toured America with the Third Concerto, Horowitz played it with Frederick Stock in Chicago, Fritz Reiner in Cincinnati, Walter Damrosch in New York, Pierre Monteux in Philadelphia, and Koussevitzky in Boston. In May 1929 he played it in Berlin with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and Mengelberg, and later played it in England with the same conductor, recording it for HMV with Albert Coates in December 1930 (Naxos 8.110696). This was the first of Horowitz's three commercial recordings of the work; he recorded it again in 1951 with Fritz Reiner, and chose the work to celebrate the golden jubilee of his American début in 1978 with Eugene Ormandy.

The 1951 recording with Reiner was made in Carnegie Hall (not during a performance, but as with the recording of Beethoven's Emperor, RCA using the hall as a recording venue); the first movement being recorded on the afternoon of 8th May 1951 and the other two movements on the afternoon of 10th May. Compared to the 1930 recording, by 1951 Horowitz's playing was far more frenetic and highly-strung. Years of touring and performing, his audiences expecting more daring and amazing feats of virtuosity at every appearance, led to a nervous collapse only two years later when Horowitz was forced to retire from public appearances for twelve years. A performance in October 1951 of Rachmaninov's Third Concerto in London, where he had not appeared since 1939, had one critic describing Horowitz's passage-work as 'now a jet of flame, now a puff of powder, now a cascade of dew…..In this sort of interpretation the executant contributes something to a composition which the composer himself did not know was in it.'

Having already lambasted a recording of the same concerto in January 1951 by Witold Malcuzynski, Lionel Salter when writing in the Gramophone about the Horowitz version accused HMV (RCA's British affiliate) of issuing 'one not only as bad, but worse'. He found the recorded balance between soloist and orchestra 'little short of farcical', complained of 'a never-ending clatter of piano tone… (nasty shallow tone it is in forte, too) and a muzz of orchestra somewhere in the background.' Whereas Salter found much to complain about the recording and performance, the critic C. G. Burke reviewed the disc in three sentences, the third of which contains hilarious hyperbole and an obverse opinion. 'It is very hard to believe that any other pianist and conductor living can eclipse the appeal of the complimentary coalescence of the recreative musical craft promulgated here with such smooth bounty in a slick, unshowy recording, masterly in proportion, and unadulterated in tonal essence save for some dampening of piano resonance.' The American Record Guide found the 1930 recording 'full of grace and lightness' whilst the 1951 version 'has all the drive and energy - and lightness - of a B-29'. This recording has always being marred by its harsh sound quality, but this new transfer, in overcoming this, also presents Horowitz's sound as somehow less frenetic and harddriven and captures some of his most dazzling virtuosity.

Jonathan Summers