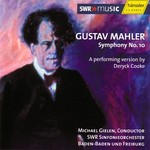

Symphony No. 10 F sharp Major (performing version by Deryck Cooke)

$35.09

Out of Stock

$35.09

Out of Stock6+ weeks add to cart

MAHLER

Symphony No. 10 F sharp Major (performing version by Deryck Cooke)

Sinfonieorchester Baden-Baden und Freibu / Michael Gielen (conductor)

[ Hanssler / CD ]

Release Date: Friday 24 March 2006

This item is currently out of stock. It may take 6 or more weeks to obtain from when you place your order as this is a specialist product.

"I can enthusiastically recommend this disc to any Mahlerite who still needs to be convinced about the viability of this score."

(Fanfare Magazine)

"Like Eliahu Inbal before him, Michael Gielen recorded a cycle of the Mahler symphonies that included the Adagio of the Tenth, only to conclude, a few years later, that Deryck Cooke's performing version of Mahler's last symphony deserved another look. Here we have the fruits of Mr. Gielen's research. Though the edition of Cooke's score used for this recording, made in March of 2005, is not specified, it is probably safe to conclude that it was the revised version, first published in 1976.

The famous Adagio has gained a couple of minutes in the years since Mr. Gielen's first recording in 1989, but it has lost none of the intensity or passion of that performance. I noted in 27:1 that Gielen's tempos for the movement established the proper relationship, as the Adagio broadened out from its initial andante pace, and that is the case with this new performance. This may seem either didactic or trivial, but it's something few conductors honor: Sir Simon Rattle, for all of his acknowledged authority in this score, employs a very expansive tempo for the opening of his Berlin performance. It is elsewhere in the movement, notably in the development, that the more expansive quality of this new recording is evident. Compared to the earlier recording, the sound production for the new performance is better balanced, if not quite as immediate. The strings are given a more natural perspective than previously, and the winds are very clearly delineated, which gives the inner voices clarity that is too often obscured. Most important, Gielen's performance practically shouts "Mahler,” and the insight he has gained through performing and recording all of the symphonies is very much in evidence.

Making the tricky rhythms of the Scherzo work while allowing the music to dance is a challenge for any conductor; Gielen manages the feat while giving the music a swagger that suits it. The warmth of the second subject finds Gielen once again in expansive mood, which is all to the good, as this genial music contrasts sharply with the almost giddy energy of the first theme; the violins sound wonderful in this section. The fidelity of the sound is again very much a factor, producing a totally convincing performance.

For those who still resist any of the performing versions of the 10th, one listen to the miniature "Purgatorio” should do the trick. Here, in just over four minutes, is Mahler at his most concentrated—one could almost suggest that Mahler invented Webern. It is definitely the fulcrum on which the entire structure of the symphony balances. This performance steers an expert course between the humorous and the grotesque.

The fourth movement, often labeled the second Scherzo, is better understood simply from its tempo marking of allegro pesante, as Mahler's military preoccupation collides with his obsession with the dance. We are not only dancing on the edge of the volcano, we are attendees at the officers' cotillion on the eve of battle. Gielen's performance teeters on the brink as he reigns in his forces, only to set them loose again. The orchestra again copes heroically with the whiplash changes in tempo and mood. The bass drum stroke that signals the transition to the finale is impressively sharp, but doesn't overpower the listener so much as command his attention.

This finale is so much like that of the Sixth, beginning in the murk and gloom; the difference is in the shimmering flute solo that lifts us out of it. That solo never fails to give me chills, and it does so here. The rest of the orchestra follows suit, and once again we are incredibly thankful to Cooke for giving us this gift—or at least for making it possible to more easily experience it. The various moods that have been visited reappear, though the darker tendencies of the opening—and of the opening Adagio's dissonant scream—assert themselves in the development. Yet, we continually return to music that must suggest our ultimate redemption—how else to characterize such beauty? Gielen's performance communicates this with playing that is refined yet passionate. The dramatic upwelling of sound in the final minutes of the movement is somewhat underplayed, as though Mahler simply needed to let go.

I lamented in my earlier review that it was a pity that Mr. Gielen had not seen fit to record one of the performing versions of the 10th. He mentions in the program notes to this disc that he had considered two versions—the Cooke and the version by Clinton Carpenter. I'm glad he chose this version, and that he reconsidered the whole issue of the 10th, since it has produced such an inspired performance, one that easily shares the top shelf with Inbal and Rattle. While the 10th may still be considered a footnote in the Mahler canon, it is the kind of footnote that illuminates and enhances. I can enthusiastically recommend this disc to any Mahlerite who still needs to be convinced about the viability of this score."

(Fanfare Magazine)