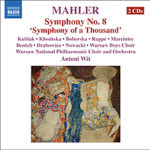

Mahler: Symphony No. 8, 'Symphony of a Thousand'

$28.00

Special Order

$28.00

Special Order3 - 6 weeks add to cart

GUSTAV MAHLER

Mahler: Symphony No. 8, 'Symphony of a Thousand'

Polish Radio Choir, Warsaw Boys Choir, Warsaw National Philharmonic Choir, Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra / Antoni Wit (Conductor)

[ Naxos / 2 CD ]

Release Date: Tuesday 9 May 2006

This item is only available to us via Special Order. We should be able to get it to you in 3 - 6 weeks from when you order it.

"Exceptional value … serious Mahlerians really should hear it"

(MusicWeb Recording of the Month Oct 2006)

Described by the composer as his "gift to the whole nation", Mahler's Eighth Symphony has had an equivocal reception even judged by the standards of his symphonies as a whole. Coming after three purely orchestral symphonies, each with its distinctive and provocative take on triumph and adversity, it might seem a throwback to his second and third symphonies, with their quirky though compelling hybrid of symphony and cantata. Yet the Eighth Symphony, in many respects, is the most integrated and organic symphony that Mahler had yet attempted - the result, in large part, of a genesis whose sheer suddenness and rapidity took even its composer by surprise.

The summer of 1906 found Mahler determined to avoid the intensive composing of previous years. Thus he arrived at his Maiernigg retreat with numerous themes for a four-movement work, but little intention of seeing them through to fruition. One such was for an orchestral movement inspired by, but not setting, the hymn 'Veni creator spiritus' - and it was the words of this hymn (or, at least, Mahler's recollection of them) that inspired him to set the text to music in a matter of days. The remaining movements of the original plan, corresponding to a symphonic slow movement, scherzo and finale, were not so much abandoned as redistributed across the setting of the final scene from Part Two of Goethe's Faust that evolved over the ensuing weeks.

The choice of texts is significant. The Whitsuntide Vesper hymn 'Veni creator spiritus', generally attributed to the ninth century cleric Hrabanus Maurus, Archbishop of Mainz, stems from a 'Dark Age' that was even more obscure a century ago than now: the Goethe text is the visionary conclusion to the philosophical second half of his greatest work; not so much a bridge from the Enlightenment to the Romantic eras as an abstraction relating to both but belonging to neither. The remoteness of both these texts from 'contemporary' aspirations made them communicable only through an all-embracing musical realisation such as Mahler was ideally equipped to undertake.

Part One sees thunderous organ chords presage the opening lines, here resplendent on full chorus [CD 1 / Track 1]. This dies down, whereupon the soloists introduce a supplicatory new theme [1/2], taken up quietly by the chorus, and leading to a forthright choral restatement of the opening theme. An ominous orchestral postlude leads into the depths [1/3], where anxious choral voices are met by a conciliatory response from the soloists. There is a brief pause [1/4], after which woodwind, brass and pizzicato strings have a crepuscular interlude, leading to a group of tranquil themes shared among the soloists [1/5]. A majestic orchestral response [1/6] sees the chorus launch an elaborate double fugue; an energetic development of the themes heard so far, joined at length by the soloists in the ascent, martial and fervent by turns, to an effulgent restatement of the opening chorus [1/7]; the beginning of a compact reprise that proceeds swiftly through the main themes so far heard. This reaches a brief climax, then robust strings [1/8] introduce the coda, in which all the musical forces are united in a final outpouring of triumph.

Part Two opens with a lengthy orchestral introduction, evoking the craggy outcrops and wild precipices described by Goethe. The two main themes (which will inform all of those subsequently heard), a questioning idea for upper woodwind over pizzicato strings and a glowing chorale-like melody for strings and lower woodwind, alternate as the music reaches a stark climax, the first theme re-emerging as a recessional. A passionate third theme breaks in [2/2], bringing with it the second theme in intensified guise. This gradually returns to the first theme [2/3], joined by the chorus representing holy Anchorites who shelter among rocky clefts. The second theme reappears, also with chorus, before an abrupt change of expression brings the arrival of Pater Ecstaticus [2/4] in a glowing apostrophe to love attained through suffering. This latter is dwelt upon by Pater Profundus [2/5], in anguished tones that utilise the third theme of the introduction.

A orchestral postlude leads to the joyful appearance of Angels and Blessed Boys [2/6], then the more reserved response of Younger Angels [2/7]. The ominous idea heard near the start of Part One is recalled [2/8], as More Perfect Angels (with solo mezzo-soprano) consider the unearthly union of Faust and Gretchen, then Younger Angels [2/9] join with Doctor Marianus [2/10] in anticipating the arrival of Faust's soul in its chrysalis state, there to await the benediction of the Queen of Heaven (Mater Gloriosa, or the Virgin Mary). The chorus, joined by Penitent Women and Una Poenitentium (Gretchen), similarly pay homage in the most beatific music of the whole work [2/11], upper strings underpinned by harp arpeggios and harmonium chords.

A sequence of solos now for three women who were present at Christ's crucifixion: Magna Peccatrix [2/12], Mulier Samaritana [2/13] and Maria Aegyptiaca [2/14], each considering the importance of repentance as the means to salvation. Una Poenitentium looks forward to the emergence of Faust in his cleansed condition [2/15], and Blessed Boys wistfully contrast their unformed state with the wisdom that Faust will impart [2/16]. Gretchen turns to await him [2/17], and Mater Gloriosa sends out her greeting from on high (the only appearance of the third soprano in the whole work). Doctor Marianus urges those on earth to yield to the redeeming gaze of their heavenly queen. The exalted mood is intensified by the chorus, before an orchestral interlude, with its magical interplay of harp and celesta, plaintively fades to silence. Now the Chorus Mysticus [2/18] gradually builds in a vast crescendo of praise to the Eternal Feminine: drawing on themes from across the work, and culminating with the return of the very opening music in a coda of exultant affirmation.

"Try to imagine the whole universe beginning to ring and resound", was how Mahler himself described the impact of these closing pages. Such was conveyed to the audience at the first two performances, given in Munich on 12 and 13 September 1910, four years after the work's completion, and according to Mahler his greatest triumph as a composer, only eight months before his death. The size of the forces arrayed led to its being dubbed 'Symphony of a Thousand', a subtitle Mahler never sanctioned but which came to represent the symphony as a musical albatross to later generations. Yet this apparent excess is essential to its nature: one which uninhibitedly combines the sacred past and the secular present in an act of confidence toward the future.

Richard Whitehouse

Tracks:

Symphony No. 8 in E flat major, "Symphony of a Thousand"