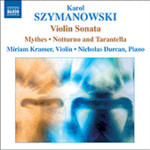

Szymanowski: Violin Sonata / Mythes / Notturne and Tarantella

$25.00

Out of Stock

$25.00

Out of StockSpecial Import add to cart

KAROL SZYMANOWSKI

Szymanowski: Violin Sonata / Mythes / Notturne and Tarantella

Miriam Kramer (violin) / Nicholas Durcan (piano)

[ Naxos / CD ]

Release Date: Wednesday 11 April 2007

This item is only available to us via Special Import.

Composed in 1904, the emotionally turbulent Violin Sonata is one of several large-scale instrumental works that emerged during Szymanowski's first phase, in which the influences of Chopin and Scriabin are combined with those of the German late-Romantics.

Karol Szymanowski (1882-1937)

Music for Violin and Piano

Although they are less central to his output than orchestral, vocal or piano music, Karol Szymanowski wrote a number of works for violin and piano, spanning his entire career; enabling a decent appreciation of his musical development from this medium alone. That development falls into four main phases: a first phase (1900-1912), in which the influences of Chopin and Scriabin, are combined with those of the German late-Romantics, notably Strauss and Reger; a second phase (1913-19), which sees the evolution of a highly individual style, drawing on the Impressionism of Debussy and early Stravinsky but also on Middle Eastern culture and folklore; a third phase (1918-24), centering on the opera King Roger and which intensifies the previous phase while anticipating that to come; and a fourth phase (1925-34), drawing freely and also imaginatively on Polish folk-music, notably that of the Tatra region, in music whose astringent harmonies and bracing rhythms reflect the composer's Polish heritage, in a personal take on the neo-Classicism then being pursued by such composers as Bartók, Stravinsky and Prokofiev.

Composed in 1904, the Violin Sonata is one of several large-scale instrumental works that emerged in Szymanowski's first phase, which also saw the first two symphonies [Naxos 8.553683] and the first two piano sonatas [Naxos 8.553867 and 8.553016 respectively]. Outwardly conventional both in its overall form and also that of each movement, the piece yet shows a thorough assimilation of its stylistic influences, as well as a confidence in writing for the difficult violin-and-piano medium that Szymanowski was to develop and refine in subsequent works.

The first movement opens with an impassioned theme that involves both instruments in a forceful dialogue. A second theme is more inward and discursive, while not lacking expressive impetus, before winding down in a pensive codetta. The development draws both of these themes into a rhapsodic yet cumulative series of exchanges that reaches a hesitant pause, only for the reprise to commence with the intensified but curtailed return of the first theme. Its successor is duly given more space to unwind, anticipating the resigned tone that is confirmed by a subdued coda. Initiated by soothing piano figuration, the slow movement unfolds as a lyrical cantilena for violin, its unbroken melodic line at length curtailed by capricious violin pizzicati and piano chords in rhythmic unison. Ending as abruptly as it began, this passes into a resumption of the lyrical music, moving towards a rapt climax that presently winds down to the tender close. The finale opens with a declamatory call to attention from both instruments, then proceeds with a purposeful theme that moves naturally into the easeful secondary melody. The brief but energetic central section features incisive motivic exchanges, before the main themes are recalled in an expressively heightened reprise then brought together in the surging coda.

Although a minor piece, the Romance (1910) is significant in that it finds the composer in the process of incorporating aspects of the musical Impressionism prevalent in his second phase, and which is exemplified in such works as the Third Symphony [Naxos 8.553684] and the First Violin Concerto [Naxos 8.553685]. The music unfolds in warmly lyrical writing, touching on greater reserves of emotion as it progresses, and twice building towards a brief but expressive apex, before concluding in a mood of gentle repose.

The Notturno and Tarantella (1915) is Szymanowski's most demonstrative work for violin and piano, though probably more frequently heard in the orchestration by the conductor Grzegorz Fitelberg [Naxos 8.553685]. The Notturno begins with lapping chords on piano and a mysterious, Oriental-sounding phrase on violin. This opens into songful writing that soon develops greater rhythmic impetus and also expressive immediacy, propelling the music to a varied recollection of its initial ideas then to a retreat back into the sombre yet sultry atmosphere from which it emerged. With barely a pause, the Tarantella launches on its impulsive course. Complementary in every respect, it unfolds with a dynamism rare in Szymanowski's music of this period, and draws both instruments into a dialogue as intense musically as it is virtuosic technically. At length, the underlying dance rhythm drives the music forward so that it reaches a decisive and scintillating close.

It was with Mythes (1915) that Szymanowski produced a work for violin and piano able to rank with the finest in the medium. He was undoubtedly aided in this through collaboration with Pawel Kochański, the Polish violinist whom the composer credited with an altogether new expressive range for the instrument, and for whom he went on to compose both of his violin concertos [Naxos 8.553685].

The first piece, La Fontaine d'Aréthuse, opens with translucent piano harmonies over which the violin spins a melodic line both ethereal and ecstatic. The music becomes more quixotic as the instruments vie with each other in spiralling arcs of sound, and yet its essential poise remains as the initial mood is regained and the music proceeds to its close with two self-effacing piano chords. The second piece, Narcisse, is a 'romance' of chaste import, the violin line floating over delicate piano figuration with a supple grace that is only partially effaced by the greater fervency of the central section. This brings a semblance of emotional climax, only for the violin to effect a heightened return to the initial music and on to a conclusion that refers to both ideas in a mood of calm benediction. The third piece, Dryades et Pan, brings the sequence to a close with music of suitably liquid energy and grace. A central section features airborne violin harmonics, and also witnesses the complex harmonic interplay of both instruments in music of improvisatory elegance that rises to a brief climax, only to dissolve in a haze of dissonance. A deft exchange of gestures, and the music vanishes into the ether.

The Berceuse d'Aïtacho Enia (1925) is the only piece for violin and piano from Szymanowski's fourth phase. Another minor work, it yet touches on the pathos that is central to the music of his last years. Over a calm and undulating piano figure, the violin unfolds a delicate melody that touches on cadential resting-points, while all the time retaining its tonal ambivalence, before reaching a subdued close.

The final piece in this collection is Kochański's transcription of the famous aria that Roxanna sings in Act Two of Szymanowski's opera King Roger [the complete opera is on Naxos 8.660062-63], and which soon established itself as a popular encore item. After a largely unaccompanied introduction, the transcription closely follows the contours of the vocal line and also its fastidious harmonic support. Rising to a sensuous climax, it subsides regretfully to a 'concert-ending' that in no sense compromises the repose of the original.

Richard Whitehouse

Tracks:

King Roger, Op. 46: Roxana's Song (arr. for violin and piano)

Lullaby, Op. 52, "La berceuse d'Aitacho Enia"

Myths, Op. 30

Nocturne and Tarantella, Op. 28

Romance in D major, Op. 23

Violin Sonata in D minor, Op. 9