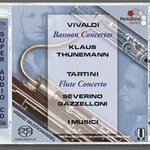

Vivaldi: Bassoon Concertos (with Tartini-Flute Concerto)

$40.00

Out of Stock

$40.00

Out of StockSpecial Import add to cart

ANTONIO VIVALDI

Vivaldi: Bassoon Concertos (with Tartini-Flute Concerto)

Klaus Thunemann (bassoon) Severino Gazzelloni (flute) / I Musici

[ Pentatone SACD / SACD ]

Release Date: Tuesday 1 May 2007

This item is only available to us via Special Import.

"The recording is clear, the pacing and tempi perfect and the overall appeal higher than you might have thought if you didn't know the repertoire. It's worth getting to know!"

(MusicWeb reviewing the original recording April 2007)

Hybrid/SACD DSD remastered Playable on all compactdisc players

"The recording is clear, the pacing and tempi perfect and the overall appeal higher than you might have thought if you didn't know the repertoire. It's worth getting to know!"

(MusicWeb reviewing the original recording April 2007)

Just as the "invention" of the organ concerto is more or less credited to George Frideric Handel, it is fair to portray Antonio Vivaldi as the pioneer of the bassoon concerto. Like its instrumental predecessor, the dulcian, the bassoon was used exclusively as a basso continuo instrument until the beginning of the 17th century, providing a basis for both the melody and harmony. In 1645, nine sonatas by G.A. Bertoli for bassoon and basso continuo were published, probably the first works written for the bassoon as a solo instrument. By 1700, the introduction and development of instrumental forms during the Baroque - such as the solo concerto and three-movement sonatas - finally announced a new era for the bassoon, in which Vivaldi was to take a leading role. Since 1704, the Venetian composer had been employed by the Ospedale della Pietà, an ecclesiastical educational institute for girls (mainly for orphans and foundlings), as maestro di violino. As such, he was also responsible for directing the sacred music. In Vivaldi's day, the orchestra formed by the girls at the Ospedale had an excellent reputation, which stretched far beyond the city limits of Venice.

Although the information from various sources remains, as before, complicated, even unclear at times, researchers assume that Vivaldi wrote his 39 surviving bassoon concertos almost exclusively for the girls in the orchestra of the Ospedale. (There are two known exceptions: RV 496 was composed for the Marquis de Morzin, and RV 502 for Giuseppe Biancardi; and two additional concertos were probably written in Bohemia.) There are two notable matters with regard to this statement: first of all, the sheer amount of concertos, and secondly, the truly excellent quality of all these entire works, which remained a constant - two observations which do not fit in with the widely held image (to which some still partially subscribe to this day) of the prolific composer Vivaldi, who usually made double and even triple use of his creative ideas. Therefore, we must conclude that, alongside the violin, the bassoon was a special favourite of Vivaldi's.

In his bassoon concertos, Vivaldi completely exhausts the technical performance possibilities of the instrument. In the fast movements, he employs the considerable range of the instrument, demanding extreme virtuosity (passage work entailing various octaves; large, consecutive leaps; and complicated arpeggios). However, in the slow middle movements, he concentrates on the cantabile passages. Virtuosity and lyricism are given equal priority in the context of the composition.

Apart from the technical demands made of the soloist, the bassoon concertos also receive a lot of attention due to the style of their composition: the works are progressive and, if you like, clearly the work of a musical pioneer. A glance at the structure of the movements provides evidence of this. Some of the ritornel themes - such as the "fading cantabile" (Bertling) of the first theme from RV 484 - are of impressive stature and certainly not the result of mass production. Also the fact that the accompaniment of the tutti is interspersed with fragments of motifs from the ritornel demonstrates his ability to grow and develop, a characteristic not generally accredited to Vivaldi. Admittedly, the concertos always keep to the same basic scheme: however, they are many and diverse, and are each developed in a distinct manner. Vivaldi was a subtle musician, who provided each chosen composition model with an individual means of survival, in many cases thanks to the individual detailing and spontaneity.

Giuseppe Tartini's (1692-1770) reputation is based mainly on his extraordinary skills as a violinist. Accordingly, he composed primarily works for the violin, although he also wrote sacred choral music. He based his style on the gallant and sensitive writing of the pre-Classical period. There is hardly any information available on the creation of his Flute Concerto in G. This does not contain any opposed themes in the first movement - as yet, it is completely indebted to late-Baroque aesthetics -, even though the tutti strings play a syncopated rhythm, countered by the flute with a more usual type of melody. In the middle movement, the flute melody rises above the strings, full of ornamentation. The work is concluded with great virtuosity in the last movement.