Symphonies Nos 1 & 2

$40.00

Special Order

$40.00

Special Order3 - 6 weeks add to cart

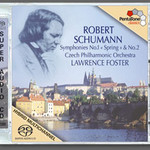

SCHUMANN

Symphonies Nos 1 & 2

Czech Philharmonic Orchestra / Lawrence Foster

[ Pentatone SACD / Hybrid SACD ]

Release Date: Tuesday 25 March 2008

This item is only available to us via Special Order. We should be able to get it to you in 3 - 6 weeks from when you order it.

"…the glowing sophistication of these notable readings carries its own special kind of authority".

Julian Haylock, International Record Review

Hybrid/SACD - playable on all compact disc machines.

"Those seeking new 'authentic' insights into these works will have to look elsewhere, but these full-blooded performances with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra in top form will, I suspect, appeal to many listeners wanting a recording of this coupling and the eventual completion of the cycle should be well worth hearing.

Strongly recommended."

Graham Williams, SA-CD.net

"I thoroughly enjoyed this CD and would be happy to return to it".

Rob Cowen, Gramophone

"A fine release!"

Robert Benson, Classicalcdreview.com

"…the glowing sophistication of these notable readings carries its own special kind of authority".

Julian Haylock, International Record Review

Beethoven, Beethoven, always Beethoven. There was just no way past him. The ninth and final symphony of the Viennese master doomed every composer who attempted to compose a work belonging to this genre. The height of the bar that Beethoven raised with his "Ode to Joy" was simply too high. What could come next after the daring integration of the human voice with the "pure" musical world of the symphony? It was to last a quarter of a century, filled with half hearted, provincial and diminutive attempts lacking in perspective, before Niels Gade, Franz Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann could inject new blood into the symphony.

At the beginning of 1841 and in only a few weeks Robert Schumann, inspired by Franz Schubert´s "Great" symphony in C major and Mendelssohn´s musical work at the Gewandhaus, and in what can only be described as creative intoxication, composed his first symphony in B major opus 38. With this work he regarded his move towards symphonic composition as accomplished: This would be his mission from now on. On the 31st of March that year the symphony was introduced to the music world as part of a Gewandhaus concert under the direction of Felix Mendelssohn. Schumann wrote "In the last few days I´ve completed a work (at least in outline) with which I´m totally at peace but which has also totally exhausted me. Just think a complete symphony - and for good measure a spring symphony - I can hardly believe it myself that it´s finished…" And this "Spring" symphony was not just the start of a new phase in the composer´s life but also a second spring for the genre symphony.

The title used by Schumann naturally brings to mind programme music par excellence. But the composer had already removed the movement titles (Start of Spring - Evening - Joyful Company - Full Spring) in the manuscript. He wanted to "depict" not to "paint". In the music one can easily comprehend the development of his poetical thinking right up to it´s fulfilment in the Finale. The "romantic" idea means the subsuming of the constituent movements under one poetic concept. Furthermore the whole symphony is concentrated towards the Finale. The "motto" for the complete work is a trumpet motive at the beginning of the first movement which appears in various guises throughout the movements - sometimes impossible to miss, sometimes nearly unrecognisable. The middle movements, an elegant instrumental Larghetto with a directly coupled five part scherzo, refuse to follow the cyclic recipe. In contrast the final movement fulfils it´s task - bringing to a close the cycle with bravura, although without large gestures and instead takes on the character of a graceful last dance.

Also in 1841 after his symphonic first born, Schumann followed a radical direction in the first version of his originally second numbered symphony in D minor number 4 opus 120. Here the cyclic thinking is brought to it´s absolute completion in which the movements, using connecting passages, are linked into an organic whole. Schumann decided 10 years later to fundamentally rework the piece with the result that the Symphony in C-Major opus 61 composed in 1845 is today known as his second (although chronologically it´s the third after the B Major and an earlier attempt in G major). Schumann wrote: "I wrote the symphony in December 1845 and still half ill [he means here his deep depression and state of anxiety] it seems to me as though one can hear this".

The work, through it´s key and motives, shows a relationship to pre-Beethoven symphonies. Perhaps this piece more than any other of Schumann´s symphonic works, shows his dilemma most clearly. This was how to fill an inherited classic, astringent, objective form structure with a subjective individual, poetically expressive will. Schumann directly attacks the sonata structure by placing the thematic material only in the introduction. The other form parts are adapted in an increasingly tiered and variable work method. The slow movement is a pure "fantasy" piece. In the scherzo Schumann creates a new expressive dimension with demonic restless passages and two markedly contrasting trios. The Adagio (after an intensive study of Bach) appears very baroque like in it´s bass line which is covered by an almost painful melody. In the finale the cyclic solution is not achieved by using the already heard themes, but by a foreign theme, a Beethoven quote (!). "Nimm sie hin denn diese Lieder" from the song cycle "An die ferne Geliebte" serves to bring the work to a powerful noisy conclusion which nonetheless sounds implausibly happy.

Tracks:

Symphony No. 1 in B flat Op. 38 (1841)

"Frühlingssymphonie" / "Spring Symphony"

Symphony No. 2 in C Op. 61 (1845-46)