Symphonies Nos. 1 & 3 Eroica

$40.00

Out of Stock

$40.00

Out of Stock6+ weeks add to cart

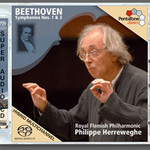

BEETHOVEN

Symphonies Nos. 1 & 3 Eroica

Royal Flemish Philharmonic / Philippe Herreweghe

[ Pentatone SACD / Hybrid SACD ]

Release Date: Sunday 1 June 2008

This item is currently out of stock. It may take 6 or more weeks to obtain from when you place your order as this is a specialist product.

"Philippe Herreweghe has the better sound, hands down, and thus is the advantage of this disc. When I finished listening twice, I simply sat back with a great feeling of satisfaction. This is good Beethoven, maybe even great"

(Audiophile Audition)

Hybrid/SACD - playable on all compact disc players

"Symphonies 1 and 3 were taped June 26-29, 2008 in the Concertgebouw, Brugge in Belgium. Producer Andreas Neubronner and balance engineer Markus Heiland have done a splendid job in capturing the rich sound of these dynamic performances; surely this Eroica is superior to the new Andrew Manze version with the Helsingborg orchestra".

Robert Benson, classicalcdreview.com

"Philippe Herreweghe has the better sound, hands down, and thus is the advantage of this disc. When I finished listening twice, I simply sat back with a great feeling of satisfaction. This is good Beethoven, maybe even great, and while it may or may not assault the sacred cows of the past-and certainly can compete with them in ways-Herreweghe is on to something here, and makes his case with thoughtful, highly musical aplomb".

Audiophile Audition, Steven Ritter

"In the present recordings of Beethoven's Symphonies Nos. 1 in C and 3 in E-flat ("Eroica") with the Royal Flemish Philharmonic, Herreweghe shows himself completely in command of all the resources of a large symphony orchestra. And he shows us something else. He knows his Beethoven".

Dr Phil Muse, Atlanta Audio Society

"The two most recent "Eroica" performances that I've heard are a study in contrast: Herreweghe's is majestically scaled, elegant, balanced; Järvi's is propulsive, light-textured, and nimble…..on the whole, I prefer Herreweghe's performances, and especially the sound production. PentaTone has provided a weighty, full, and deep production that renders Järvi's RCA job lightweight by comparison. That could be said to apply to the performances as well".

Christopher Abbot, Fanfare

It is all too easy to forget that when Ludwig van Beethoven presented his early symphonies to the Viennese public at the beginning of the 19th century, the genre there had already lost much of its allure. But the facts speak for themselves: by around 1795, well-known symphonic composers such as Haydn, Gyrowetz and Vanhal had relegated the symphony to oblivion and were concentrating on other artistic projects. And it seemed the new generation of Viennese composers were not the least bit interested in mastering this genre. The reason for this waning popularity was the slow erosion of court culture. Although every 18th-century Austrian court had employed its own orchestra, such excesses were being pruned vigorously in the aftermath of the Enlightenment. Furthermore, the Viennese concert society no longer operated regularly at the end of the 18th century, so public symphonic concerts were not being organised. Anyone preferring financial security to artistic integrity was therefore better advised to write operas, this being pretty much the safest choice for composers in those days, despite the fluctuating taste of the average Viennese music lover. After all, a commercially successful opera did a great deal more for one's fame than a solidly constructed string quartet or an innovative symphonic work. This explains Beethoven's repeated (but unsuccessful) attempts - right up to 1807 - to persuade the directors of various city theatres to give him a job as an opera composer.

Even before this period, however, the symphony was not really uppermost in Beethoven's mind; he showed conspicuously little interest in the genre when he went to Vienna in 1792 to take composition lessons from Haydn. At that time, Haydn was planning his second journey to London, a city in which various concert societies vied with each other to put on public concerts featuring symphonic works. Even so, Beethoven seemed to be totally oblivious of Haydn's symphonic plans (which were to result in the superb London symphonies). Later, when Beethoven was trying to build up his career as a pianist, the symphony still did not occupy a prominent place in his compositional agenda, and that is why the ideas he put on paper in 1795 for a symphony in C major remained as sketches.

It would be going too far to claim that Beethoven had, up to the age of 30, absolutely no interest in the genre. In addition to the above mentioned social and cultural factors, there were obviously artistic reasons for Beethoven's relatively late development in this direction. Of course, a stylistic purist such as Beethoven would understandably feel a certain artistic diffidence when having to compare his symphonic works with those of Haydn and Mozart. More importantly, however, Beethoven was engaged in an aesthetic exercise of the mind. It so happens that the trend set by Haydn and Mozart was one of increasing autonomy. Although it had been customary in the past to deliver symphonies in related groups, the future lay in the creation of symphonies that were unrelated to each other. The ambitious tone found in Haydn's last London symphonies meant they had already left the group feeling behind. Mozart's last three symphonies also showed a move in the direction of symphonic emancipation, so it was just a case of waiting for someone of a radical nature to come along - someone who was enough of a megalomaniac to produce the first totally independent symphony. And Beethoven was certainly a megalomaniac. When that abnormally tense opening chord in his First Symphony sounded on 2 April 1800, the musical history of the nineteenth century really had begun.

Beethoven's Symphony No. 1 in C is thus much more than the result of his first foray into this genre. The moment of creation is in itself a reason for viewing this symphony as a symbol of a new era in which bourgeois taste was demanding an example of 'Einzelwerke'. More or less the first romantic orchestral work, this symphony throws up a number of problems in the musical structure, and then aims to 'solve' them in the subsequent movements. Thus, the first thing that one notices is the thematic relationship: the main theme in the Allegro con brio contains an interval of four notes that expands into an octave, providing thematic material for the other movements. Another point of interest is Beethoven's revision of the classical symphonic form. For example, he marks the Menuetto with Allegro molto e vivace which has the effect of replacing the rather dance-like minuet with the more virulent brio of a scherzo. The Finale deviates from the norm too; not a rondo, but a true sonata that provides precisely the weight Beethoven intended for this symphony. However, we certainly do not have to wait until the finale to hear something of genius. The slow introduction already demonstrates that a skilful narrator is at work: after two harmonically unexpected chord changes, the music starts 'searching' for the opening melody. This slow introduction is therefore not a sound aperitif à la Haydn; it is an essential part of the musical process. And then there is the instrumentation: this also serves to distance Beethoven from his predecessors. For one thing, the wind players have a much more creative role and for another, the instrumental timbres are unusually striking.

Five years later, Beethoven's plea for symphonic emancipation resulted in a first success, the Symphony No. 3 in E flat, opus 55, the 'Eroica'. This monstre sacré of the early romantic orchestral literature is not easy to place in time: before the official premiere in 1805 there had already been a whole series of tryout concerts in which Beethoven permitted a number of corrections and alterations to be made. The reason for holding these "workshop concerts" was of course the heroic nature of the Eroica; this Third Symphony is justifiably regarded as an epic composition. The examples used to prove this are well-known. The Allegro con brio fans out delightfully, giving rise to: the ever-present main theme, an equivocal subsidiary melody, the sudden appearance of a new theme halfway through the movement, an out-of-step rhythm, a misleading recapitulation of the opening theme and an ambitious coda. In contrast to all this grandeur, the funeral march that follows is introverted and serene but it nevertheless manages to undermine our expectations: once by launching into an expressive fugato and a second time by catching the dirge completely unawares as the major key is introduced. Already announced in the First Symphony, the driving scherzo of the third movement mainly makes use of dynamic surprises: after 91 introverted bars, a sudden fortissimo appears from nowhere. Finally, the fourth movement; this is still puzzling musicologists as it defies all the conventional definitions of form, being much more like a series of playful variations - an exceptional way to crown this heroic symphony. And that is why Beethoven's Eroica has reached its status of immortality because, despite the heroic origins of this symphony (as is well known, it was dedicated to Napoleon in a fit of adoration), Beethoven does not make the mistake of producing pure pomposity. There are of course moments of ceremonial glory and serious pathos but there are also vivid, moving, playful and even humoresque passages, all of which contribute to this symphony's complexity. It is precisely this interplay of diverse mood changes, meticulously tuned to each other, that makes Beethoven's Third Symphony the locus classicus for every orchestral composition - even today.

Tracks:

Symphony No.1 in C, Op.21

Symphony No.3 in E flat, Op.55 "Eroica"